Pitting Don Bradman Against Leaders of Related Sports:

An Investigation

Part II

Bradman on deck travelling

to England with the Australian

women’s tennis team, 1938

International Soccer

International matches got underway in earnest from the early-1900s, with the present governing body, FIFA, being founded in 1904. Yet the first official World Cup was not held until 1930 (proceeding on a four yearly basis), with the Olympics being the vehicle for international matches before then. In 1934, a total of 36 teams applied to compete in the World Cup, with 16 coming through after qualifying matches. By 1966, 70 countries took part in qualifying; and in 2002 a total of 199 teams attempted to qualify with 32 doing so – the same as in 2018.

Of those players with careers prior to 1930, only 3 had reached the qualifying threshold of 30 goals, adopted by both Walters and myself, and only another 8 had done so ten years later. Yet by early-June 2014 (prior to the World Cup that year), a total of 220 players had reached this threshold, and by end of 2020 this had increased by around one-third, giving a field of 303 players for analysis.

During this six and a half year interval, the dominance ratings of the leading 20 players has risen a little – by between 0.15 and 0.28.

Kettle – findings for soccer, top 20 to end 2020

|

|

Career Span |

Goals |

Matches |

Goals/Match |

Z Score |

| 1 |

Just Fontaine (France) |

1953-60 |

30 |

21 |

1.429 |

4.63 |

| 2 |

Vivian Woodward (England) |

1903-14 |

73 |

53 |

1.377 |

4.37 |

| 3 |

Poul Nielsen (Denmark) |

1910-25 |

52 |

38 |

1.368 |

4.32 |

| 4 |

Gunnar Nordahl (Sweden) |

1942-48 |

43 |

33 |

1.303 |

3.99 |

| 5 |

Sven Rydell (Sweden) |

1923-32 |

49 |

43 |

1.140 |

3.16 |

| 6 |

Ernest Wilimowski (Poland) |

1934-42 |

34 |

30 |

1.133 |

3.13 |

| 7 |

Sándor Kocsis (Hungary) |

1948-56 |

75 |

68 |

1.103 |

2.97 |

| 8 |

Edward Acquah (Ghana) |

1956-64 |

45 |

41 |

1.098 |

2.94 |

| 9 |

Gerd Müller (West Germany) |

1966-74 |

68 |

62 |

1.097 |

2.94 |

| 10 |

Kunishige Kamamoto (Japan) |

1964-77 |

75 |

76 |

0.987 |

2.38 |

| 11 |

Ferenc Puskás (Hungary) |

1945-56 |

84 |

89 |

0.944 |

2.16 |

| 12 |

Pauli Jørgensen (Denmark) |

1925-39 |

44 |

47 |

0.936 |

2.12 |

| 13 |

Faas Wilkes (Netherlands) |

1946-61 |

35 |

38 |

0.921 |

2.05 |

| 14 |

Nathaniel Lofthouse (England) |

1950-58 |

30 |

33 |

0.909 |

1.99 |

| 15 |

Silvio Piola (Italy) |

1935-52 |

30 |

34 |

0.882 |

1.85 |

| 16 |

Imre Schlosser (Hungary) |

1906-27 |

59 |

68 |

0.868 |

1.78 |

| 17 |

Jassem Al-Huwaidi (Kuwait) |

1992-2002 |

63 |

74 |

0.851 |

1.69 |

| 18 |

Ernest Pol (Poland) |

1956-65 |

39 |

46 |

0.848 |

1.68 |

| 19 |

“Pelé” (Brazil) |

1957-71 |

77 |

92 |

0.837 |

1.62 |

| 20 |

Luigi Riva (Italy) |

1965-74 |

35 |

42 |

0.833 |

1.60 |

Source: rsssf.com/miscellaneous/international goals

The above list displays four conspicuous features: the strong presence of Scandinavian players, with four in the top twelve; only one of the players have been in action since the late-1970s; only one Brazilian player is present (Pelé) despite its wealth of elite talent, and none at all from the powerhouses of Spain, Portugal and Argentina. To satisfy curiosity about omissions of various legendary attacking players, the matches played and goals scored by some of the more prominent are noted below:

Brazil

Neymar: 64g-103m (2010-20), Ronaldo: 62g-98m (1994-2011), Romário: 55g-70m (1987-2005),

Zico: 48g-71m (1976-86), Zizinho: 30g-53m (1942-57)

Spain

Alfredo Di Stéfano (mainly Spain, also Argentina): 29g-37m (1947-61), David Villa: 59g-98m (2005-17)

Portugal

Cristiano Ronaldo: 102g-170m (2003-20), Eusebio: 41g-64m (1961-73)

Argentina

Lionel Messi: 71g-142m (2005-20), Diego Maradona: 34g-91m (1977-94)

Uruguay

Luis Suárez: 63g-116m (2007-20)

Netherlands

Johan Cruyff: 33g-48m (1966-77)

France

Michel Platini: 41g-72m (1976-87)

England

Tom Finney: 30g-76m (1946-58), Bobby Charlton: 49g-106m (1958-70),

Jimmy Greaves: 44g-57m (1959-67), Alan Shearer: 30g-63m (1992-2000)

Scotland

Denis Law: 30g-55m (1958-74)

Sophisticated measures have been devised that indicate a soccer player’s overall worth to his team, given his position (role) on the field and reflecting his estimated influence on each match played. Statistics also exist on the number of passes a player makes in a game and his assists given to goal scorers. But these rating schemes are a fairly recent innovation (created during the last two to three decades), and cannot be applied retrospectively as there are invariably insufficient observations of a given player’s performance. So far, such measures have also been limited in systematic application to certain club competitions (such as the English Premier League) and to FIFA World Cup matches – not being applied it seems to many (if any) other competitive international matches such as the UEFA European Championship or to “friendly” matches.

The notion of dead runs in cricket has a parallel in soccer and also rugby union. However, end of season team standings for regional competitions and for World Cup groups/pools are sometimes decided on the differential between goals or points scored and conceded. Although this is decisive only occasionally, the potential for a team to find itself in such a position at season’s end, or just prior to a knock-out stage of a competition, is often present for a good deal of the time. So there is usually a motivation for a team to press a strong goals or points advantage during most of their matches in tournaments (as distinct from “friendly” matches). To cite one illustrative case: in the 2014 soccer World Cup, the USA who were surprisingly tied on points with Portugal, went through to the knock-out stage on superior goal difference.

In soccer, I have found a suitable record for the leader, Just Fontaine of France, though for hardly any other prominent player (England’s Tom Finney is a rare exception). To identify a dead or potentially dead goal, the record needs to state the state of play when a player scored his goals – the goal difference immediately after he scored and, desirably also, at what time during the match. For Fontaine, the first piece of information, and whether the match was during a competition, is readily available through Wikipedia. Taking a potentially dead goal to be one that is scored when the team is already two goals ahead of the opposition in a tournament, one-third of his goals in FIFA World Cup and UEFA Euro Cup competition – 7 of 21 – come into this category. And one-third of his goals scored in friendly fixtures – 3 of 9 – were definitely “dead” ones.

Intuitively, these might seem to be relatively high ratios, but whether this is actually so would need testing for a sample of other prominent players and adjustments then made to the whole field on that basis. Outside of World Cup competitions, identifying dead goals/points scored would mean carefully trawling though and interpreting a great number newspaper of magazine accounts. Possibly, Fontaine’s dominance rating would rise (above 4.63 as estimated) instead of fall – though it is barely conceivable that his rating would raise to a level threatening DGB’s 5.77. If it is assumed that all other players in the qualifying field of 303 players have definite dead goals amounting to 40% of those they each scored, as opposed to 33% being assumed for Fontaine, then his dominance rating would rise to 5.45 – still short of DGB.

International Rugby Union

Although the first international match occurred as far back as 1871 (England versus Scotland), a substantial set of fixtures had to wait for four decades with the five nations tournament beginning in 1910 (adding Wales, Ireland and France). This supplemented the Australia-New Zealand matches which had begun in 1903. New Zealand-South Africa matches followed from 1921 and Australia-South Africa matches from 1933. The four yearly World Cup competition started comparatively recently, in 1987, which greatly expanded the number of qualifying players. With the removal of formal restrictions on payments to players, the game became a professional sport from 1995.

Similar to soccer, some rating schemes have been devised to reflect a player’s influence on a match (such as the “RPI” scheme, applied to international and club players), but these are also recent developments. The readily available long-term measures are career points scored and the constituents of tries, penalties, conversions and drop goals. The focus here is on the aggregate measure: total points scored per game played in; tries alone seems too restrictive.

Partly due to the generally cramped nature of play, taking place on a field a little smaller than a standard soccer pitch but with one-third more players on each side (15 rather than 11), the leading points scorers since the inception of international matches have predominantly been those taking penalties and conversion attempts. I have applied a minimum of 130 points instead of 200 by Walters. This is in order to bring highly prominent try scorers more into the field, such as the following who have scored all of their points through tries: New Zealand’s Jonah Lomu (1994-2002) with 185 points, Uruguay’s Diego Ormaechea (1979-99) with 183, France’s Vincent Clerc (2002-13) with 170, Wales’ Ieuan Evans (1987-98) with 161, Ireland’s Keith Earls (2008-present) and South Africa’s Jaque Fourie (2003-13) both with 160, England’s Will Greenwood (1997-2005) with 155, Australia’s Tim Horan (1989-2000) with 140, and Russia’s Andrei Kuzin (1997-2011) with 130.

The careers of the great majority of prominent points scorers date from the 1980s, though the first qualifier arrives a decade after the end of WW2 in the form of New Zealand’s famous full-back, Don “the boot” Clarke (1956-64), scoring 207 points in his 31 games.

The 130 points threshold, together with updating to end of 2020, produces a qualifying total of 252 players, between them having represented 23 countries. The games and points totals include any for the British Lions and British Barbarian sides.

Kettle – findings for Rugby Union, top 15 to end 2020

|

|

Country |

Span |

Games |

Points |

Points/Game |

Z Score |

| 1 |

Simon Hodgkinson |

England |

1989-91 |

14 |

203 |

14.50 |

2.53 |

| 2 |

Dan Carter |

New Zealand |

2003–15 |

112 |

1598 |

14.27 |

2.46 |

| 3 |

Grant Fox |

New Zealand |

1985–93 |

46 |

645 |

14.02 |

2.39 |

| 4 |

Jannie de Beer |

South Africa |

1997-99 |

13 |

181 |

13.92 |

2.36 |

| 5 |

Andrew Mehrtens |

New Zealand |

1995–2004 |

70 |

967 |

13.81 |

2.33 |

| 6 |

Diego Domínguez |

Italy |

1989-2003 |

76 |

1010 |

13.29 |

2.17 |

| 7 |

Esteban R. Segovia |

Spain |

2004-07 |

22 |

285 |

12.95 |

2.07 |

| 8 |

Jonny Wilkinson |

England |

1998–2011 |

97 |

1246 |

12.85 |

2.04 |

| 9 |

Gonzalo Quesada |

Argentina |

1996–2003 |

38 |

486 |

12.79 |

2.02 |

| 10 |

Michael Lynagh |

Australia |

1984–95 |

72 |

911 |

12.65 |

1.98 |

| 11 |

Ayumu Goromaru |

Japan |

2005-15 |

56 |

708 |

12.64 |

1.98 |

| 12 |

Jared Barker |

Canada |

2000-04 |

18 |

226 |

12.56 |

1.95 |

| 13 |

Paul Grayson |

England |

1995-2004 |

32 |

400 |

12.50 |

1.93 |

| 14 |

Toru Kurihara |

Japan |

2000-03 |

28 |

347 |

12.39 |

1.90 |

| 15 |

Federico Todeschini |

Argentina |

1998-2008 |

21 |

256 |

12.19 |

1.84 |

Source: Rugby Union/Players and Officials/ESPN Scrum

Updating, combined with the shift to a lower qualifying threshold, introduces one new player to the top 15 (Jannie de Beer) whilst one drops out (Kurt Morath of Tonga, 2009-19). For the others listed, this produces an uplift in the ratings ranging from 0.37 to 0.45, equating to increases of 15% to 32%.

On the issue of points scored when the opposition has very little prospect of avoiding defeat (“dead points”), there is a similar difficulty as with soccer of identifying these. Prior to well documented records of World Cup competitions from 1999 onwards, of the Six Nations tournament (Northern Hemisphere) from 2000, and of the Tri Nations series (Southern Hemisphere) from 2007 (with Argentina joining in 2012), identification of these points means resort to careful interpretation of whatever newspaper and magazine articles have to offer.

Golf – The “Majors”

The analysis of winners extends back to the inception of each of the four Majors: the British Open from 1860, the US Open from 1895, the US PGA from 1916 and the US Masters from 1934.

The all-time basis of the analysis means that comparing players on their number of strokes per round is problematic. This would require a satisfactory way of reconciling changes to course length and layout, as well as to “advances” in the design of clubs.

Up to the end of 2020, there are 90 one-time winners who have also attained at least one 2nd place or at least two 3rd/4th place finishes, and they are included in a qualifying field of 173 players. Updating from early-June 2014, and including these once-only winners, has the effect of substantially enhancing Walters’ dominance ratings – rising in the upper reaches of the top 19 by 0.89 to 1.70 (equating to 47% – 60%) and lower down by 0.69 to 0.82 (equating to 72% – 160%). The effect of updating alone is very small, giving rises of only 0.01 to 0.03, except for Tiger Woods who is the only golfer listed to have added to his wins since mid-2014, and only by one.

Kettle – findings for golf, top 20 to end 2020

Source: Wikipedia – List of men’s major championships winning golfers

Three players are present in the list with pre-WW1 careers, perhaps surprising as only two of the Majors were in operation during that period. And there are only two golfers whose careers enter the present century – Tiger Woods and Phil Mickelson – which seems to indicate an intensifying (greater evenness) of competition – as with most professional sports over time, including Test cricket. A reduction over successive eras in the extent of variation around the overall average of participants’ performance in a sport is to be expected, owing to two factors:

- A general improvement in playing standards occurring with the maturing of a sport; stemming from a more general awareness of advances in technique, a standardisation of training exercises, a spread of individually-directed coaching to eliminate faults and suchlike.

- A ceiling coming into effect as the elite performers approach the limits of human endeavour.

Perhaps more than any of the other sports considered, with golf the difference is slight in demonstrated ability between most of the top twenty players of the world and those outside who lie within the top one or two hundred. Take the calibre of the following golfers, for example, who have secured up to four wins as against those with five to seven wins listed above:

3-4 wins: Billy Casper, Larry Nelson, Hale Irwin, Ernie Els, Vijay Singh, Rory McIlroy.

1-2 wins: Roberto De Vicenzo, Tony Jacklin, Johnny Miller, Tom Weiskopf, Tom Kite, Ben Crenshaw,

Greg Norman, Fred Couples, Bernhard Langer, Sandy Lyle, Corey Pavin, Nick Price,

José María Olazábal, Adam Scott, Sergio Garcia.

And of those who haven’t won a Major, I saw the following in action live, practising and on the course, during the 1970s/80s who made me fell just as lucky as watching some of those already noted:

Neil Coles, Brian Barnes, Peter Butler, Peter Oosterhuis, Martin Green, Mark McNulty,

Manuel Piñero.

Men’s Grand Slam Tennis – Singles

Of the four Grand Slam tournaments, Wimbledon and the US Open began in 1877 and 1881 respectively, with the Australasian Open following two decades later in 1905 (becoming the Australian Open from 1927) and the French Open in 1925 (previously, as from 1891, being restricted to members of national clubs). The US Championships continued unabated during both World Wars, unlike the other three. Each of them is examined from their inception.

Updating from early-June 2014, and including one-time winners who, in addition, have at least one other Grand Slam finals appearance or at least two semi-finals appearances (comprising 50 of the 65 one-time winners) produces a qualifying field of 135 players. Whilst those forming the updated top 27 remain unchanged from 2014, the list sees the rise of Nadal from third to equal first place with his 7 additional wins, a major move by Djokovic from equal 21st to 3rd place with his 11 additional wins, and Federer sharing first place having had 3 further wins.

Updating and the associated larger field (56 more players) means that for those listed under Djokovic there is a small rise on Walters’ dominance ratings – ranging from 0.01 for Sampras in 4th place and increasing to 0.28 for those sharing 22nd place.

Kettle – Findings for men’s tennis, top 27 to end 2020

|

|

Country |

Winning Span |

Wins |

Z Score |

| 1= |

Roger Federer |

Switzerland |

2003-18 |

20 |

4.69 |

|

Rafael Nadal |

Spain |

2005-20 |

20 |

4.69 |

| 3 |

Novak Djokovic |

Serbia |

2008-20 |

17 |

3.84 |

| 4 |

Pete Sampras |

USA |

1990-2002 |

14 |

2.99 |

| 5 |

Roy Emerson |

Australia |

1961-67 |

12 |

2.43 |

| 6= |

Rod Laver |

Australia |

1960-69 |

11 |

2.15 |

|

Björn Borg |

Sweden |

1974-81 |

11 |

2.15 |

| 8 |

Bill Tilden |

USA |

1920-30 |

10 |

1.87 |

| 9= |

Fred Perry |

England |

1933-36 |

8 |

1.30 |

|

Ken Rosewall |

Australia |

1953-72 |

8 |

1.30 |

|

Jimmy Connors |

USA |

1974-83 |

8 |

1.30 |

|

Ivan Lendl |

Czechoslovakia |

1984-90 |

8 |

1.30 |

|

André Agassi |

USA |

1992-2003 |

8 |

1.30 |

| 14= |

William Renshaw |

England |

1881-89 |

7 |

1.02 |

|

Richard Sears |

USA |

1881-87 |

7 |

1.02 |

|

William Larned |

USA |

1901-11 |

7 |

1.02 |

|

René Lacoste |

France |

1925-29 |

7 |

1.02 |

|

Henri Cochet |

France |

1926-32 |

7 |

1.02 |

|

John Newcombe |

Australia |

1967-75 |

7 |

1.02 |

|

John McEnroe |

USA |

1979-84 |

7 |

1.02 |

|

Mats Wilander |

Sweden |

1982-88 |

7 |

1.02 |

| 22= |

Laurence Doherty |

England |

1902-06 |

6 |

0.74 |

|

Anthony Wilding |

New Zealand |

1906-13 |

6 |

0.74 |

|

Jack Crawford |

Australia |

1931-35 |

6 |

0.74 |

|

Don Budge |

USA |

1937-38 |

6 |

0.74 |

|

Boris Becker |

Germany |

1985-96 |

6 |

0.74 |

|

Stefan Edberg |

Sweden |

1985-92 |

6 |

0.74 |

Source: Wikipedia – List of Grand Slam men’s singles champions

Although the listing goes down to six wins, there are some extremely talented omissions, in certain cases due to turning professional. Some of the most prominent and interesting are:

- Norman Brookes (Australia) – the first non-British player to win the Wimbledon men’s singles, doing so in 1907 and again in 1914; was also a major force in Davis Cup competition, being instrumental with Wilding in gaining Australasia five of its six trophies between 1907-19.

- William Johnston (USA) – From 1915-25, gained two US Open and one Wimbledon win; and runner-up to Tilden in the US Open on five occasions. With Tilden, he secured seven consecutive Davis Cup trophies.

- André Gobert (France) – French national singles champion in 1911 and 1920; took the singles title at the British Covered Court Championships five times during 1911-22; and was an all-comers finalist at Wimbledon in 1912.

- William Laurentz (France) – instinctive and brilliant, if sometimes erratic. When only 16 years old, defeated the 27 year old colossus Anthony Wilding in five sets in the final of the 1911 French Covered Court Championships, and played in the Davis Cup a year later. Despite losing the sight in one eye from a freak tennis accident in 1912, he continued playing at the highest level – winning the World Hard Court Singles in 1920 (defeating Gobert in the final) and the World Covered Court Championship in 1921.

- Bunny Austin (England) – during the 1930s, runner-up twice at Wimbledon and once at the French Open. Was the last British player to reach the Wimbledon final until Andy Murray in 2012.From 1933-36, Austin and Fred Perry were at the forefront in winning the Davis Cup for Britain, in the final defeating France, USA twice and then Australia.

- Jaroslav Drobný (Czechoslovakia) – between 1946 and ’54, once winner and twice runner-up at Wimbledon, twice winner and three times runner-up at the French Open. Ranked in the world top 10 from 1946 to ’55. Gained a total of 147 singles titles.

- Manuel Santana (Spain) – with an all-court artistry, gained titles at the French (twice), Wimbledon and US Open during 1961-66. Played a key role in getting Spain through to the ultimate “Challenge” round of the Davis Cup in 1965 and ’67.

- Gerald Battrick (Wales) – displayed a model all-court game on en-tout-cas courts from a late-teenager into his mid-twenties; at age 24, winning the 1971 British Hard Court Singles Championship.

- Ramesh Krishnan (India) – a flowing stylist with just a hint of top-spin on his forehand and usually a little under-cut on the backhand. Highly prominent as a junior, winning the Wimbledon and French junior titles in 1979 at age 18. Consistently, a high quality performer in Grand Slam events from age 20-26 and would have gained some titles with a stronger service.

- Guillermo Vilas(Argentina) – from 1975-82, winning singles at the Australian (twice), French and US Opens, and four times a runner-up in Grand Slam singles events. Rated third best of all-time on clay courts, after Borg and Nadal.

- John Alexander (Australia) – youngest player ever to play in the Final Round of the Davis Cup, doing so at age 17 and 5 months, and competing from 1968-80 with a 17-9 singles wins-losses record.

- Henri Leconte (France) – arguably the most brilliant and entertaining player not to secure a Grand Slam title. Finalist in the French Open in 1988, and represented France in Davis Cup competition for 13 consecutive years from 1982.

- Andy Murray (Scotland) – in addition to his one US Open and two Wimbledon triumphs, runner-up eight times in grand slam events, all accomplished during 2008-16 from age 21.

Some who turned professional

- Vincent Richards (USA) – a prodigy who turned pro in 1926 at age 23, by then a four time semi-finalist in the US Open singles, initially at age 19. Ranked 3rd in the world for 1925 and 6th for 1926. Won the US Pro tournament four times between 1927 and 1933.

- Pancho Gonzalez (USA) – following two US Open titles in 1948-49, played pro tennis until the mid-1960s, winning many tournaments in America and England. At the very top of the sport from 1954-61. Great natural athletic ability plus lightning reflexes.

- Jack Kramer (USA) – turned pro after winning two US Opens and Wimbledon in 1946 and ‘47. One of the initial world class players to consistently adopt a serve and volley approach to singles.

- Lew Hoad (Australia) – turned pro following wins during 1956-57 over compatriots in the Australian and French Opens and at Wimbledon (twice), and having been a finalist in the US Open. From 1958-63, a runner-up 7 times in pro slam tournaments in the USA, France and England.

Women’s Grand Slam Tennis – Singles

Updating the qualifying field from early-June 2014 to incorporate the 24 subsequent grand slam events, and including 28 of the 50 one-time winners (based on the same criterion as for the men), produces a qualifying field of 102 players. The composition of the leading 21 players is unaltered from 2014, with just one change in position – Serena Williams moving up from 6th to 2nd place having secured six additional wins.

Williams aside, the dominance ratings of Walters are raised by between 0.28 at the bottom of the list to 0.45 at the top – equating to increases of 12% (top) to 255% (bottom). This is due very largely to the enlarged qualifying field, containing 33 additional players since mid-2014.

Kettle – findings for women’s tennis, top 21 to end 2020

|

|

Country |

Winning Span |

Wins |

Z Score |

| 1 |

Margaret Court |

Australia |

1960-73 |

24 |

4.18 |

| 2 |

Serena Williams |

USA |

1999-2017 |

23 |

3.97 |

| 3 |

Steffi Graf |

Germany |

1987-99 |

22 |

3.76 |

| 4 |

Helen Wills Moody |

USA |

1923-38 |

19 |

3.13 |

| 5= |

Chris Evert |

USA |

1974-86 |

18 |

2.92 |

|

Martina Navratilova |

Czechoslovakia |

1978-90 |

18 |

2.92 |

| 7 |

Billie Jean King |

USA |

1966-75 |

12 |

1.65 |

| 8= |

Maureen Connolly |

USA |

1951-54 |

9 |

1.02 |

|

Monica Seles |

Yugoslavia |

1990-96 |

9 |

1.02 |

| 10= |

Molla Bjurstedt Mallory |

USA |

1915-26 |

8 |

0.81 |

|

Suzanne Lenglen |

France |

1919-26 |

8 |

0.81 |

| 12= |

Dorothea Lambert Chambers |

England |

1903-14 |

7 |

0.60 |

|

Maria Bueno |

Brazil |

1959-66 |

7 |

0.60 |

|

Evonne Goolagong |

Australia |

1971-80 |

7 |

0.60 |

|

Venus Williams |

USA |

2000-08 |

7 |

0.60 |

|

Justine Henin |

Belgium |

2003-07 |

7 |

0.60 |

| 17= |

Blanche Bingley Hillyard |

England |

1886-1900 |

6 |

0.39 |

|

Nancye Wynne Bolton |

Australia |

1937-51 |

6 |

0.39 |

|

Margaret Osborne duPont |

USA |

1946-50 |

6 |

0.39 |

|

Louise Brough |

USA |

1947-55 |

6 |

0.39 |

|

Doris Hart |

USA |

1949-55 |

6 |

0.39 |

Source: Wikipedia – List of Grand Slam women’s singles champions

Of omissions from this list, those possessing outstanding talent include pre-WW1 pioneers, Lottie Dodd and Charlotte Cooper Sterry of England, plus the USA’s Hazel Hotchkiss. A number of prodigies are also absent: May Sutton, who won the US singles in 1904 at age 17 and a winner twice at Wimbledon in the next two years – being the only overseas player to win there until after WW1; Christine Truman, who won the French Open at age 18 and was a finalist at the US Open and Wimbledon by age 20; more recently, Hana Mandlíková, Arantxa Sánchez Vicario, Martina Hingis and Maria Sharapova (all with 4 or 5 grand slam wins), whilst Tracy Austin’s precocious career was cut short by a series of injuries and a serious automobile accident after winning the US Open at age 16 and again two years later.

In contrast, Althea Gibson made a late and stunning breakthrough, being one of the first Black athletes to cross the colour line of international tennis. From age 28, within the space of three years she achieved five wins at three Grand Slam events and was also a finalist at the Australian Open, before venturing to make a living from promotional and exhibition matches.

Highly notable also is the absence of Kitty McKane (2 Grand Slam wins), undoubtedly England’s best player in pre-WW2 times. She was one of only three players (along with Helen Wills and Elia Álvarez) capable of posing a serious threat to the pre-eminent Suzanne Lenglen who reigned from 1919 until turning pro in late-1926.

Squash – British Open Championship, Men

For much of the time since its inception in 1931, this tournament has been regarded as the unofficial world championship. It is now widely considered to be one of the two most prestigious of the game, along with the World Open Championship (established in 1976 for men, and in 1979 for women).

Up until 1947, the format was similar to the early phase of tennis singles at Wimbledon and the US Open, with the reigning champion standing by to play the winner of the rest of the field in the “Challenge Round”. With the British Open, this challenge consisted of the best of three matches. Subsequently, a standard knock-out format has been used. Apart from the WW2 period, the tournament has been staged annually – except for 2010 and ’11 when sponsor support fell through and in 2020 owing to the presence of the Covid-19 virus.

The qualifying field of 21 players includes 6 of the 9 one-time winners who have, in addition, made at least one finals or two semi-finals appearances.

Kettle – findings for men’s squash, top 13 to end 2020

|

|

Country |

Winning Span |

Wins |

Z Score |

| 1 |

Jahangir Khan |

Pakistan |

1982-91 |

10 |

2.47 |

| 2 |

Geoff Hunt |

Australia |

1969-81 |

8 |

1.70 |

| 3 |

Hashim Khan |

Pakistan |

1951-58 |

7 |

1.31 |

| 4= |

Jonah Barrington |

England |

1967-73 |

6 |

0.92 |

|

Jansher Khan |

Pakistan |

1992-97 |

6 |

0.92 |

| 6 |

FD Amer Bey |

Egypt |

1933-38 |

5 |

0.54 |

| 7= |

Mahmoud Karim |

Egypt |

1947-50 |

4 |

0.15 |

|

Azam Khan |

Pakistan |

1959-62 |

4 |

0.15 |

|

David Palmer |

Australia |

2001-08 |

4 |

0.15 |

| 10= |

Abou Taleb |

Egypt |

1964-66 |

3 |

-0.24 |

|

Nick Matthew |

England |

2006-12 |

3 |

-0.24 |

|

Grégory Gaultier |

France |

2007-17 |

3 |

-0.24 |

|

Mohammed El Shorbagy |

Egypt |

2015-19 |

3 |

-0.24 |

Source: Wikipedia – British Open Squash Championships

Most conspicuous is the presence of Pakistani and Egyptian players – comprising 12 of the qualifying field and 8 of those listed above – both countries having a long tradition of high quality club competition. The Khan dynasty of Pakistan ruled the British Open through three relatives, initially during the 1950s and early-1960s, and later through Jahangir Khan in an unbroken 10 year stretch from the early-1980s. (Jansher Khan was unrelated to these players.)

Owing chiefly to the highly consistent, inexhaustible and enduring play of Jonah Barrington and Geoff Hunt, none of a gifted Pakistani quartet of Aftab Jawaid (3 finals), Gogi Alauddin (2 finals), Mohibullah Khan (1 final) and Hiddy Jahan (1 final) was able to clinch the title. And their compatriot, Mohammed Yasin had to withdraw from the 1974 final due to an ankle injury incurred during his semi-final in overcoming the wizardry of Qamar Zaman, having in the previous round defeated the reigning champion Jonah Barrington. Two Australians are also highly prominent without attaining the title: the deceptive left hander, Cam Nancarrow (2 finals) and Rodney Martin (3 finals) who took the mighty Jahangir Khan to five games in the 1989 final.

Squash – British Open Championship, Women

At its inception in 1922 and for the next five years, this tournament took the form of a series of “round robin” matches prior to the semi-finals stage. Since 1927, a conventional knock-out format has been adopted.

Of the field of 25 qualifying players to end of 2020 (including all 8 one-time winners), the main features are the dominance of English and Australian players – 12 and 7 respectively – and, as with the men, long-series of wins by a quintet of players. The performance of Heather McKay, with 16 straight finals wins, is unparalleled in the sport – against whom gaining one game (in best of 5 game encounters) was regarded as a triumph! Witnessing her British Open final in 1976 against the second seed, Sue Newman, she was in control throughout in an undemonstrative way. Her game was stylish and neat, without unnecessary power; moving usually unhurried in a flowing manner about the court.

McKay lost only two matches in her entire career: in 1960, at the quarter-finals stage of the New South Wales tournament; and in 1962, at age 20, the Scottish Open final. She was unbeaten in tournament play from then right through to 1981 when she retired at age 40. There are strong runs of success also by Margot Lumb with 5 straight wins in the 1930s, Janet Morgan with 10 straight in the 1950s, Susan Devoy with a string of 7 wins from the mid-1980s, and Michelle Martin with a string of 6 wins in the 1990s.

Kettle – findings for women’s squash, top 13 to end 2020

|

|

Country |

Winning Span |

Wins |

Z Score |

| 1 |

Heather McKay |

Australia |

1962-77 |

16 |

3.58 |

| 2 |

Janet Morgan |

England |

1950-59 |

10 |

1.85 |

| 3 |

Susan Devoy |

New Zealand |

1984-92 |

8 |

1.28 |

| 4 |

Michelle Martin |

Australia |

1993-98 |

6 |

0.70 |

| 5= |

Nicol David |

Malaysia |

2005-14 |

5 |

0.41 |

|

Margot Lumb |

England |

1935-39 |

5 |

0.41 |

| 7= |

Vicki Hoffman (Cardwell) |

Australia |

1980-83 |

4 |

0.13 |

|

Rachael Grinham |

Australia |

2003-09 |

4 |

0.13 |

| 9= |

Joyce Cave |

England |

1922-28 |

3 |

-0.16 |

|

Nancy Cave |

England |

1924-30 |

3 |

-0.16 |

|

Cecily Fenwick |

England |

1926-31 |

3 |

-0.16 |

|

Susan Noel |

England |

1932-34 |

3 |

-0.16 |

|

Joan Curry |

England |

1947-49 |

3 |

-0.16 |

Source: as for men’s squash

The most eminent player never to gain the title is Sue Cogswell of England, runner-up in 1974, 1979 and 1980. She won the British National Championship five times during 1975-80 and was a finalist in the 1979 World Open.

Including performances in the World Open Championship, starting in 1976 (the only other tournament on a par with the British Open) raises the number of qualifying men players by only half a dozen, to become 27. The top dominance rating rises moderately from 2.47 to 2.92 (Jahangir Khan in both cases), though still way down on DGB in cricket. These combined statistics have not been used as the best set of results to quote due to the lengthy gap in the two tournaments’ inception dates (nearly half a century). It would unfairly and substantially reduce the ratings for five great players: Hashim Khan, Barrington, Bey, Karim and Azam Khan.

The same combined analysis has been done for women’s squash (there being a 57 year gap in their two inception dates), giving an increase again of half a dozen qualifying players. The dominance ratings of British Open greats, McKay (retiring after only one World Open entry) and Morgan fall by 0.46 and 0.41, although McKay remains top at 3.12. Big movers up are David (to 2nd place), and Fitz-Gerald and Sherbini (to 6th and 7th places). But, again, the combined ratings still pose no threat to DGB.

Given the small numbers making up the qualifying field in squash (21 and 25 players) – and the substantial differences for some of the other sports examined – a comment is called for as to whether a wide disparity matters in the size of the various fields. (Cricket has a field of 403 players and the other sports range between 100 and 300.)

There is no reason for a systematic correlation to exist between the size of a qualifying field and the size of the resulting ratings for the most prominent players. Whilst increasing the field to include less strong performers inevitably reduces the overall average (the Mean), the magnitude of the Standard Deviation is also affected, and in unpredictable way; and both these factors enter the calculation of the dominance ratings. How much the Standard Deviation alters depends on exactly how the shape (or pattern) of the distribution of performance values varies between qualifying fields of different sizes. The direction of Z Score change, and by how much it changes, is vitally influenced by this.[i]

With the British Open in squash, when all appearances in the final are included, the qualifying field would rise to from 21 to 53 players and the dominance ratings for all of the top 13 players increase; whereas for women’s squash the field would increase from 25 to 29 players and the ratings rise for six of the top 13 but fall for the other seven.

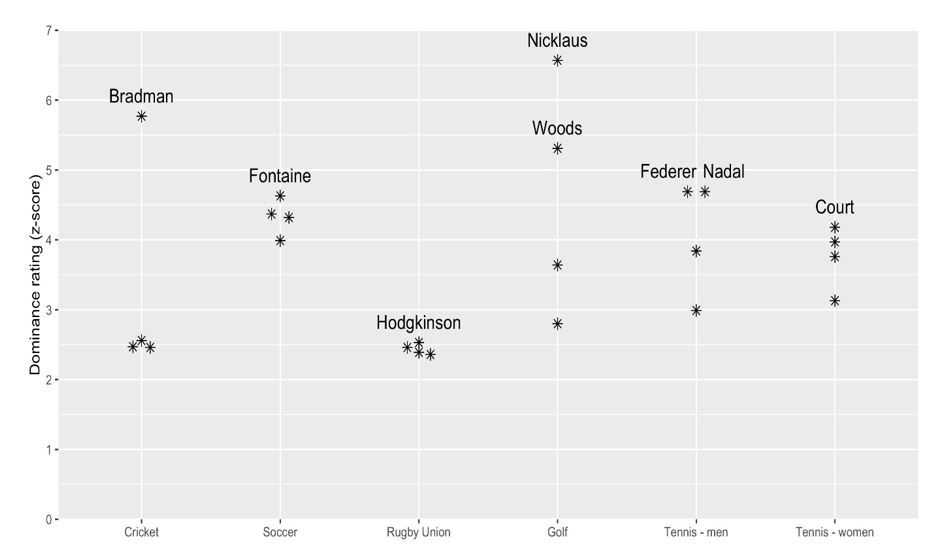

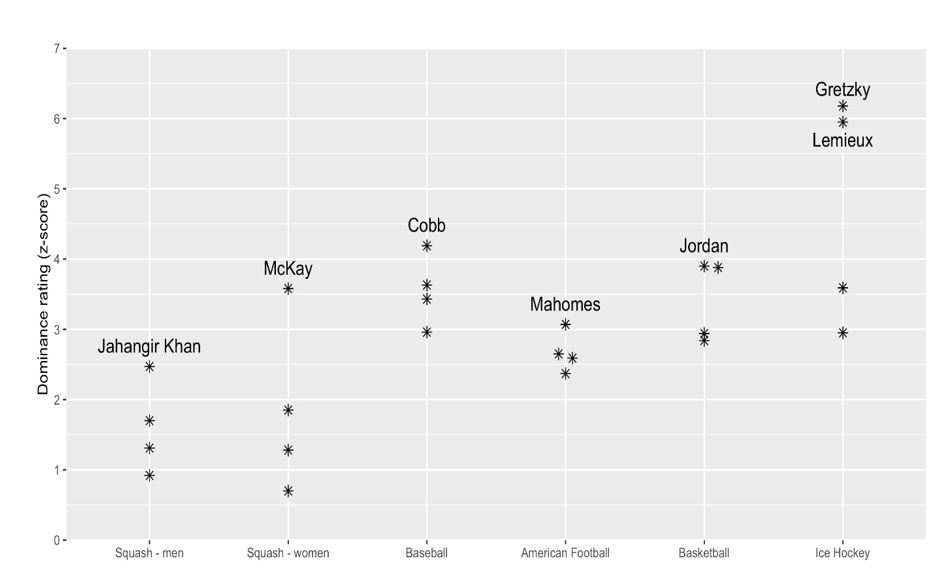

Across the first ten sports looked at, taking the 1st, 6th and 10th rated players, their ratings are set out below. No consistent pattern emerges.

| Player |

|

|

|

|

Tennis – |

Tennis – |

Squash – |

Squash – |

| Position |

Cricket |

Soccer |

Rugby |

Golf |

Men |

Women |

Women |

Men |

| 1st |

5.77 |

4.63 |

2.53 |

3.64 |

4.69 |

4.18 |

3.58 |

2.47 |

| 6th |

2.45 |

3.13 |

2.17 |

2.38 |

2.15 |

2.92 |

0.41 |

0.54 |

| 10th |

2.12 |

2.38 |

1.98 |

1.96 |

1.30 |

0.81 |

-0.16 |

-0.24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Field |

403 |

303 |

252 |

173 |

135 |

102 |

25 |

21 |

End Note

[i] In some instances, the resulting rise in the value of the Standard Deviation is sufficient to more than offset the reduced value of the Mean and produces a reduced Z Score. Thus, with cricket, when using a 1,500 runs qualifying threshold rather than 2,000s (and retaining dead runs for all players), DGB’s Z Score falls a little: becoming 6.603 instead of 6.635 (the Means are respectively 38.512 and 40.033, and the Standard Deviations are respectively 9.304 and 9.032). And when dead runs are excluded for all players, DGB’s Z Score falls by nearly the same amount, from 5.796 to 5.768. In contrast, with rugby union, using 130 points as the qualifying threshold instead of 200 points increases the Z Scores for the leading players (doing so by 0.286 to 0.344); the resulting rise in the value of the Standard Deviation being insufficient to offset the reduction in the value of the Mean.

PART 3 follows

from Cricket Web https://ift.tt/3yjwlaq